Chapter 9 - Consistency and Consensus (Part One)

· 15 min readNotes from Chapter 9 of Martin Kleppmann's 'Designing Data-Intensive Applications' book. This chapter is split into two parts.

In this chapter, we focus on some of the abstractions that applications can rely on in building fault-tolerant distributed systems. One of these is Consensus. Once there's a consensus implementation, applications can use it for things like leader election and state machine replication.

Table of Contents

Consistency Guarantees #

We've discussed eventual consistency in some of the earlier chapters as one of the consistency guarantees provided by some applications. It means that even though there might be delays in replicating data across multiple nodes, the data will eventually get to all nodes.

However, it is a very weak guarantee as it doesn't say when the replicas will converge, it just says that they will converge.

There are stronger consistency guarantees that can be provided, which we'll touch on in this chapter, but these come at a cost. These stronger guarantees often have worse performance or are less fault-tolerant than systems with weaker guarantees.

Linearizability #

The idea behind Linearizability is that the database should always appear as if there is only one copy of the data. This means that making the same request on multiple nodes should always give the same response as long as no update is made between those requests.

It is also a recency guarantee, meaning that the value read must be the most recent or up-to-date value, and is not from a stale cache. Basically, as soon as a client successfully completes a write, all other clients must see the value just written.

If one client's read returns a new value, all subsequent reads must also return the new value.

Note: In the book, Linearizability is said to also be known as atomic consistency, strong consistency, immediate consistency or external consistency. However, Google's Cloud Spanner has a different idea and distinguishes between some of those terms. This distinction is explained in another post.

Linearizability vs Serializability #

Linearizability is a recency guarantee on reads and writes of a single object. This guarantee does not group multiple operations together into a transaction (meaning it cannot protect against a problem like write skew, where a transaction makes a write based on a value it read earlier that has now been updated by another concurrently running transaction).

Serializability is an isolation property of transactions that guarantees that transactions behave the same as if they had executed in some serial order i.e. each transaction is completed before the next one starts. There is no guarantee on what serial order these transactions appear to run in, all that matters is that it is a serial order.

When a database provides both serializability and linearizability, the guarantee is known as strict serializability or strong one-copy serializability. I believe external consistency and strict serializability provide the same guarantees.

Two Phase-Locking and Actual Serial Execution are implementations of serializability that are also linearizable. However, serializable snapshot isolation is not linearizable, since a transaction will be reading values from a consistent snapshot.

Question: If serializable snapshot isolation is well implemented by ensuring that it detects writes in a transaction that may affect prior reads (from a consistent snapshot) or that it detects stale reads, wouldn't that make it linearizable as one of these transactions will be aborted and will thus preserve the recency guarantee?

Answer: I'm guessing the risk here is that the stale read might have returned a value now being used outside of the database, which then violates the linearizability guarantee.

Note that a stale read is not a violation of serializability, see here. If Transactions A & B are concurrent and Transaction A commits before Transaction B, serializability is still preserved if the database makes it look like the operations in Transaction B happened before those in Transaction A. The key thing is that the transactions appear to be executed one after the other.

Relying on Linearizability #

As good as linearizability is as a guarantee, it is not critical for all applications. However, there are examples of where linearizability is important for making a system work correctly, and we'll cover them here.

Locking and leader election #

A system with a single-leader replication model must ensure that there's only ever one leader at a time. One way to implement leader election is by using a lock. All the eligible nodes start up and try to acquire a lock and the successful one becomes the leader.

This lock must be linearizable: once a node owns the lock, all the other nodes must see that it is that node that owns the lock.

Apache ZooKeeper and etcd are often used to implement distributed locks and leader election.

Constraints and uniqueness guarantees #

When multiple users are concurrently trying to register a value that must be unique, each user can be thought of as acquiring a lock on that value. E.g. a username or email address system.

We see similar issues in examples like ensuring that a bank account never goes negative, not selling more items than is available in stock, not concurrently booking the same seat on a flight, or in a theater for two people. For these constraints to be implemented properly, there needs to be a single up to date value (the account balance, the stock level, the seat occupancy) that all nodes agree on.

However, note that some of these constraints can be treated loosely and are not always critical, so linearizability may not be needed.

Implementing Linearizable Systems #

Seeing that linearizability means the system behaves as if there is only one copy of the data, the simplest way to implement it will be to actually have just one copy of the data. However, that won't be fault-tolerant if the node that has the single copy becomes unavailable.

Since replication is the most common way to make a system fault-tolerant, we'll compare different replication methods here and discuss whether they can be made linearizable.

-

Single-leader replication (potentially linearizable): If we make every read from the leader or from synchronously updated followers, the system has the potential to be linearizable. However, there is no absolute guarantee as the system can still be non-linearizable either by design (because it uses snapshot isolation) or due to concurrency bugs.

Using the leader for reads also implies that there is an assumption that we'll always know who the leader is. Issues like split-brain can mean that a single-leader system can violate linearizability.

- Multi-leader replication (not linearizable): These systems are generally not linearizable since they can process writes concurrently, and the writes are typically asynchronously replicated to other nodes. It means that clients can view different values of a register (single object) if they read from different nodes.

- Consensus Algorithms (linearizable): We haven't dealt with this yet but these systems are typically linearizable. They are similar to single-leader replication, but they contain additional measures to prevent stale replicas and split-brain. As a result, consensus protocols are used to implement linearizable storage safely. Zookeeper and Etcd work this way.

-

Leaderless replication (probably not linearizable): Recall from Chapter 5 that these systems typically require quorum reads and writes where w + r > n. While these can be linearizable, they are almost certainly non-linearizable under certain circumstances, like when "Last write wins" is used as the conflict resolution method based on time-of-day clocks. These are typically non-linearizable because we know that clock timestamps are not guaranteed to be consistent with the actual ordering of events due to clock skew. Another circumstance where non-linearizability is almost guaranteed is when sloppy quorums are used.

Even with strict quorums, there is the possibility of non-linearizability due to concurrency bugs. If we have 3 nodes in a cluster and set w = 3 and r = 2, the quorum condition is met. However, if a client is writing to 3 nodes and two clients concurrently read from 2 of those 3 nodes, they may see different values for a register as a result of network delays in writing to all the nodes.

However, it is possible to make these dynamo-style quorums linearizable at the cost of reduced performance. To do this, a reader must perform read repair synchronously before returning results, and a writer must read the latest state of a quorum of nodes before sending its write.

The Cost of Linearizability #

While linearizability is often desirable, the performance costs mean that it is not always an ideal guarantee.

Consider a scenario where we have two data centers and there's a network interruption between those data centers:

- In a multi-leader database setup, the operations can continue in each data center normally since the writes can be queued up until the network link is restored and replication can happen asynchronously.

- In a single-leader setup, the leader must be in one of the data centers. Therefore, clients connected to a follower data center will not be able to contact the leader and cannot make any writes, nor any linearizable reads (their reads will be stale if the leader keeps getting updated). An application that requires linearizable reads and writes will become unavailable in the data centers which cannot contact the leader.

- Clients that can contact the leader data center directly will not witness any problems, since the application continues to work normally there.

The CAP Theorem #

The CAP theorem is a popular theorem in Distributed Systems that is often misunderstood. It describes a trade-off in building distributed systems. In relation to the scenario above, this trade-off is as follows:

- If an application requires linearizability and some replicas are disconnected from other replicas due to a network problem, then those replicas cannot process requests while they are disconnected: the replicas must either wait until the network problem is fixed or return an error. These replicas are then unavailable.

- If the application does not require linearizability, it can be written in a way that each replica can process requests independently even when disconnected from other replicas. Therefore, the application can remain available in the face of a network problem, but the behaviour is not linearizable.

In the original definition of the CAP Theorem, the behaviour described for Consistency is linearizability. Availability means that any non-failing node must return a response that contains the results of the requested work i.e., not a 500 error or a timeout message.

Therefore, in the face of network partitions or faults, a system has to choose between either total availability or total linearizability. That's the CAP Theorem in simple terms.

Applications that do not require linearizability are more tolerant of network problems since the nodes can continue to serve requests.

Note that while the CAP Theorem has been useful, the definition is quite narrow in scope (it only considers Linearizability as the consistency model and network partitions (i.e. nodes in a network disconnected from each other) as the only types of faults, it says nothing about network delays or dead nodes.

You can read a critique of the CAP theorem in this article, which also proposes alternative ways to analyze systems.

Linearizability and network delays #

Fault tolerance is not the only reason for dropping linearizability, performance is another reason why it sometimes gets dropped.

Interestingly, RAM on a modern multi-core CPU is not linearizable. This means that if a thread running on one CPU core writes to a memory address, a thread on another CPU core is not guaranteed to read the latest value written (unless a fence or memory barrier is used).

From StackOverflow:

A memory fence/barrier is a class of instructions that mean memory reads/writes occur in the order you expect. For example a 'full fence' means all reads/writes before the fence are committed before those after the fence.

This happens because every CPU core has its own memory cache and store buffer, and memory access goes to the cache by default. Changes are asynchronously written out to main memory. Accessing data in the cache is faster than going to the main memory, so this feature is useful for good performance on modern CPUs.

We can't say that this tradeoff was made for availability purposes, because we wouldn't expect on CPU core to continue to function properly while disconnected from the rest of the computer.

Linearizability is always slow, not just during a network fault. There's a proof in this paper that if you want linearizability, the response time of read and write requests is at least proportional to the uncertainty of delays in the network.

The response time will certainly be high in networks with highly variable delays. Weaker consistency models can be much faster than linearizability and as it is with everything, there's always a tradeoff.

In Chapter 12, there are some approaches suggested for avoiding linearizability without sacrificing correctness.

Ordering Guarantees #

Ordering has been mentioned a lot in this book because it is such a fundamental idea in distributed systems. Some of the contexts in which we've discussed it so far are:

- For single-leader replication. The main purpose of the leader is to determine the order of writes in the replication log i.e. the order in which followers apply writes. Without a single leader, we can have conflicts due to concurrent operations.

- Serializability: Serializability is about ensuring that transactions behave as if they were executed in some sequential order.

- Timestamps and clocks in distributed systems are an attempt to introduce order into a disorderly world e.g. to determine which one of two writes happened later.

Ordering and Causality #

One of the reasons why ordering keeps coming up is that it helps preserve causality. With causality, an ordering of events is guaranteed such that cause always comes before effect. If one event happened before another, causality will ensure that that relationship is captured i.e. the happens-before relationship. This is useful because if one event happens as a result of another one, it can lead to inconsistencies in the system if that order is not captured. Some examples of this are:

- If a question leads to an answer, then an observer should not see the answer before the question.

- When a row is first created and then updated, a replica should not see the instruction to update the row before the creation instruction.

- When we discussed snapshot isolation for transactions, we mentioned that the idea is for a transaction to read from a consistent snapshot. Consistent here means consistent with causality i.e. when we read from a snapshot, the effects of all the operations that happened causally before the snapshot was taken are visible in that snapshot, but no operations that happened causally afterward can be seen.

A system that obeys the ordering imposed by causality is said to be causally consistent. For example, snapshot isolation provides causal consistency, since when you read some data from it, you must also be able to see any data that causally precedes it (assuming it has not be deleted within the transaction).

The causal order is not a total order #

If elements are in a total order, it means that they can always be compared. That is, with any two elements, you can always see which one is greater and which is smaller.

With a partial order, we can sometimes compare the elements and say which is bigger or smaller, but in other cases the elements are incomparable. For example, mathematical sets are not totally ordered. You can't compare {a, b} with {b, c}.

This difference between total order and a partial order is reflected when we compare Linearizability and Causality as consistency models:

Linearizability

We have a total order of operations in a linearizable system. If the system behaves as if there is only one copy of the data, and every operation is atomic (meaning we can always point to before and after that operation), then we can always say which operation happened first.

Causality

Two operations are ordered if they are causally related (i.e. we can say which happened before the other), but are incomparable if they are concurrent. With concurrent operations, we can't say that one happened before the other.

This definition means that there is no concurrency in a linearizable database. We can always say which operations happened before the other.

The version history of a system like Git is similar to a graph of causal dependencies. One commit often happens after another, but sometimes they branch off, and we create merges when those concurrently created commits are combined.

Linearizability is stronger than causal consistency #

The relationship between linearizability and causal order is that linearizability implies causality. Any system that is linearizable will preserve causality out of the box.

This is part of what makes linearizable systems easy to understand. However, given the cost of linearizability that we've discussed above, many distributed systems have dropped linearizability.

Fortunately, linearizability is not the only way of preserving causality. Causal consistency is actually the strongest possible consistency model that does not slow down due to network delays, and also remains available in the face of network failures. The caveat here is that in the face of network failures, clients must stick to the same server, given that the server captures the effect of all operations that happened causally before the partition.

Capturing causal dependencies #

Causal consistency captures the notion that causally-related operations should appear in the same order on all processes—though processes may disagree about the order of causally independent operations - Jepsen

For a causally consistent database, when a replica processes an operation, it needs to ensure that all the operations that happened before it have already been processed; if a preceding operation is missing, the system must hold off on processing the later one until the preceding operation has been processed.

The hard part is determining how to describe the "knowledge" of a node in a system. If a node had seen the value of X when it issued the write Y, X and Y must be causally related.

We discussed 'Detecting Concurrent Writes' earlier where we focused on causality in a leaderless datastore and detecting concurrent writes to the same key in order to prevent lost updates. For causal consistency though, we need to go beyond just keeping track of a single key, but instead tracking causal dependencies across the entire database.

To determine causal ordering, the database needs to keep track of which version of the data was read by an application.

Sequence Number Ordering #

A good way of keeping track of causal dependencies in a database is by using sequence numbers or timestamps to order the events. This timestamp can be a logical clock which is an algorithm that generates monotonically increasing numbers for each operation. These sequence numbers provide a total order meaning that if we have two sequence numbers, we can always determine which is greater.

The important thing is to create sequence numbers in a total order that is consistent with causality meaning that if operation A causally happened before B, then the sequence number for A must be lower than that of B. We can order concurrent operations arbitrarily.

With single-leader databases, the replication log defines a total order of write operations that is consistent with causality. Here, the leader can assign a monotonically increasing sequence number to each operation in the log. A follower that applies the writes in the order they appear in the replication log will always be in a causally consistent state.

Noncausal sequence number generators #

In a multi-leader or leaderless database, generating sequence numbers for operations can be done in different ways such as:

- Ensuring that each node generates an independent set of sequence numbers e.g. if we have two nodes, one node can generate even numbers while the other can generate odd numbers.

- A timestamp from a time-of-day can be attached to each operation. We've discussed why this is unreliable previously*.*

- We can preallocate blocks of sequence numbers. E.g node A could claim a block of numbers from 1 to 1000, and node B could claim the block from 1001 to 2000.

However, while these options perform better than pushing all operations through a single leader which increments the counter, the problem with them is that they these sequence number are not consistent with causality. They do not capture ordering across different nodes.

If we used the third option, for example, an operation numbered at 1100 on node B could have happened before operation 50 on node A if they process a different number of operations per second. There is no way to capture that using these methods.

Lamport Timestamps #

This is one of the most important topics in the field of distributed systems. It’s a simple method for generating sequence numbers across multiple nodes that is consistent with causality.

The idea here is that each node has a unique identifier, and also keeps a counter of the number of operations it has processed. The Lamport timestamp is then a pair of (counter, nodeID). Multiple nodes can have the same counter value, but including the node ID in the timestamp makes it unique.

Lamport timestamps provide a total ordering: if there are two timestamps, the one with the greater counter value is the greater timestamp; if the counter values are the same, then we pick the one with the greater node ID as the greater timestamp.

Quoting the book, what makes Lamport timestamps consistent with causality is the following:

Every node and every client keeps track of the maximum counter value it has seen so far, and includes that maximum on every request. When a node receives a request or response with a maximum counter value greater than its own counter value, it immediately increases its own counter to that maximum.

With every operation, the node increases the maximum counter value it has seen by 1.

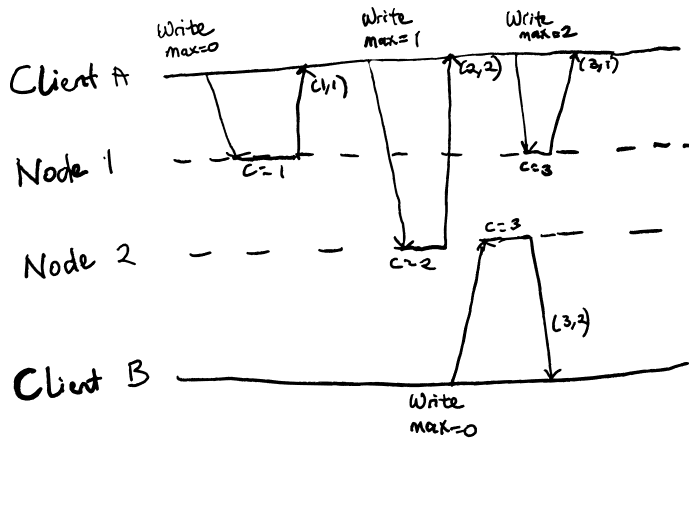

Consider the diagram below:

Figure 1 - Lamport Timestamps Illustration.

In this figure, the nodes and clients initially have a counter value of 0:

- When client A first writes to node 1, node 1 increases its counter value to 1. (1, 1)

- Client A then writes to node 2, providing node 2 with its counter value of 1. Node 2's current counter value is 0, so it first sets its value to 1, increases it to 2 for the new operation and then returns the new value. (2, 2)

- When client B sends its request to node 2, node 2 has a greater counter value than client B, so it increases its current value to 3 for the new operation and returns it to client B. (3, 2)

- Finally, client A writes to node 1 and that returns a new counter value. (3, 1)

A possible ordering of these operations is (1,1) -> (2, 2) -> (3, 1) -> (3,2), if in the case of the same counter value, our ordering scheme gives precedence to the node with the lower ID value.

This ordering showcases a limitation of Lamport timestamps. Even though operation (3,2) appears to complete before (3,1), the ordering does not reflect that.

The fact that those two have the same counter value means that they are concurrent and the operations do not know about each other, but Lamport timestamps must enforce a total ordering. With the ordering from Lamport timestamps, you cannot tell whether two operations are concurrent or whether they are causally dependent.

Basically, if two events are causally related, the Lamport timestamp ordering will always obey causality. But if one event appears before another in the ordering, it does not mean that they are causally related.

Version Vectors can help distinguish whether two operations are concurrent or whether one causally depends on the other, but Lamport timestamps have the advantage that they are more compact.

Aside: I think Lamport timestamp ordering is also sufficient to provide sequential consistency.

Further Reading:

- Distributed Agreement on Random Order – Fun with Lamport Timestamps

- Consistency, causal and eventual

Timestamp ordering is not sufficient #

Although Lamport timestamps are great for defining a total order that is consistent with causality, they do not solve some common problems in distributed systems.

The key thing to note here is that they only define a total order of operations after you have collected all the operations. If one operation needs to decide right now whether a decision should be made, it might need to check with every other node that there's no concurrently executing operation that could affect its decision. Any of the other nodes being down will bring the system to a halt, which is not good for fault tolerance.

For example, if two users concurrently try to create an account with the same username, only one of them should succeed. It might seem as though we could simply pick the one with the lower timestamp as the winner and let the one with the greater timestamp fail. However, if a node needs to decide right now, it might simply not be aware that another node is in the process of concurrently creating an account, or might not know what timestamp the other node may assign to the operation.

It's not enough to have a total ordering of operations, it's also important to know when the order is finalized i.e. what that order is at each point in time.

In the second part of these notes, we'll look at ways to solve the challenge of knowing the order of operations at each point in time.

Last Updated: 15-12-2022.